Flash Fiction Festival 2021: the Virtual’ing

Hi friends. We’ve once again partnered with our buddies over at A Novel Idea to host the Flash Fiction Festival. Given the state of the apocalypse we are all currently living in, this year it will be virtual. As much as we’d love to see your beautiful and darling faces in person (like last year’s party), we are psyched to be able to extend this opportunity to people all over the world. Also, it will be like having a flash fiction version of the boxes in the Brady Bunch, so gratitude for all the good things.

Hi friends. We’ve once again partnered with our buddies over at A Novel Idea to host the Flash Fiction Festival. Given the state of the apocalypse we are all currently living in, this year it will be virtual. As much as we’d love to see your beautiful and darling faces in person (like last year’s party), we are psyched to be able to extend this opportunity to people all over the world. Also, it will be like having a flash fiction version of the boxes in the Brady Bunch, so gratitude for all the good things.

This space will serve as the landing site for all Festival updates. So make sure that you keep your eyes on this site for new info.

Dates and Schedule:

Our Flash Fiction Festival will be the last weekend of February on the 27th and 28th. Both days will start at 10:00 AM and end at 6:30 PM. Your ticket gives you admission to the whole day, or you can come and go as you please (no pressure! only pleasure!).

Saturday the 27th:

10:00 – 11:30: Writing Workshop with Kathy Fish

11:30 – 12:15: Free write time with a provided prompt (only if you want to use it!)

12:30 – 1:30: Panel: Fantasy, Sci-Fi, Myth, and Horror in Flash Fiction

1:45 – 2:15: Poetry Palate Cleanser Readings

2:30 – 3:30: Panel: Memoir and Nonfiction in Flash Prose

3:30 – 4:00: Break

4:00 – 5:30: Writing Workshop with Jane-Rebecca Cannarella

5:45-6:30: Readings

Sunday the 28th:

(just kidding about the foes part)

10:00 – 11:30: Writing Workshop with K.B. Carle

11:45 – 12:15: Free write time with a provided prompt (only if you want to use it!)

12:30 – 1:30: Panel: Hermit Crab and Borrowed Form in Flash Fiction

1:30 – 2:15: Poetry Palate Cleanser featuring poets specializing in micro poems & more

2:30 – 3:30: Panel: Micro Flash

3:30 – 4: 00: Break

4:00 – 4:45: Readings

Make sure to get your tickets ASAP. Your purchase comes with all kinds of perks. As always, if you are facing any kind of financial hardships please message either HOOT (info@hootreview.com) or A Novel Idea (books@anovelideaphilly.com), and we are happy to work with you and help.

Get your tickets here!

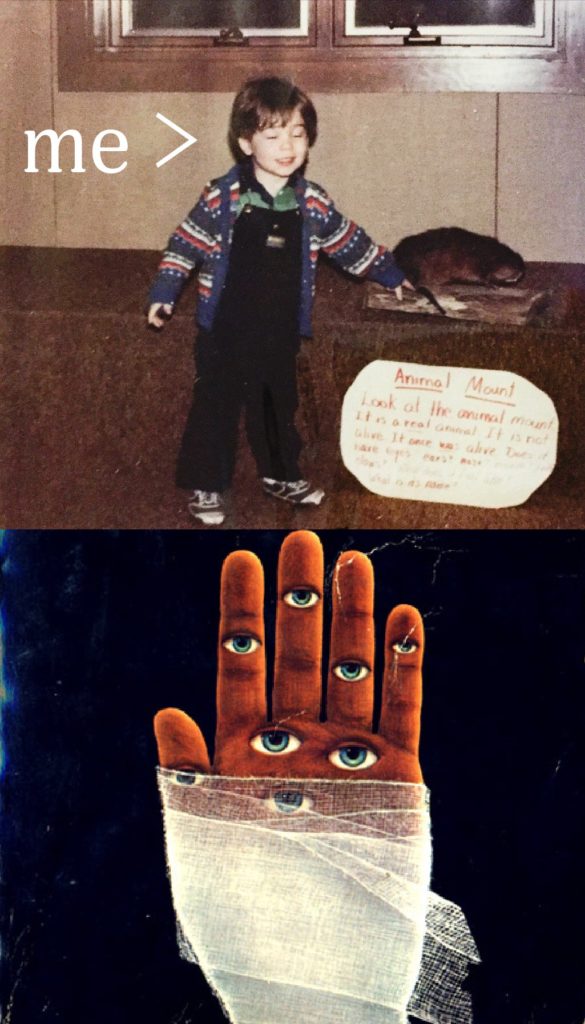

Elliot Polinksy on Stephen King

I’m ten years old, my family’s moved to a new neighborhood near the edge of the city and it feels distant, suburban. My friends are the old place, where my childhood heart is too. I’ve been reading books since birth but the new, arguably stubborn isolation of my days opens a moment where reading books is flatly the most important thing in my world. In the early nineties, a new mass-market trade paperback Stephen King novel cost $5.95, if I remember. From my parents, I received a five dollar weekly allowance. As we speak I feel a really faint, impossibly strong nostalgia around the weekly ritual of locating an extra buck plus tax so I could purchase another novel on Saturday morning. Even though the constellation of memories (they feel both sensory and abstract) are vague—like I don’t know how the hell I would get that money— they make my whole mind feel like it’s ten again. Zap. Anyway, I’d walk up to Encore Books and browse happily before grabbing a volume and walking home, so excited about the magic in the bag slopping back and forth against my hip. All that year I read Stephen King novels at a rate of roughly one per week. Misery, The Dark Half, The Tommyknockers, Different Seasons, Pet Cemetery, The Shining, It (def more than a week), The Stand (likewise)— and I read like a fucking beast, all the time, a ragged book in my hands during any corner of the day: for example, in middle school, between classes, we’d walk the halls in lines, and when we reached a doorway the first kid would step out, hold the door for everyone else, and re-join the line at the end. Another whole-mind-zap-back: reading The Dark Half (my favorite) while holding the door for thirty or so kids, then feeling jarred uncomfortably when it was time to keep moving. It’s not only Stephe King. That same year I read Les Miserables and Anna Karenina and it never occurs to me to distinguish between high and low literature. All the stories make me equally happy. All I think about is reading.

Around that time I start writing stories. The first one tells of a misunderstood witch who lives near the ragged train tracks and the next few are all re-writes of Brothers Grim fairy tales— I dig those latter but feel that they beg more explanation, I roam around thinking on them: for example Rumplestilskin, where a gnome locks a woman in a room and she’ll have to stay with him if she can’t guess his name. Why would he do that? I write a version where his crude motives are made clear. I write more fairy tales, more or less harsh all of them, and then print them on my family’s dot matrix printer. And then, because it will be years before I recognize and seek to break the pride-shame dichotomy that’s accompanied my creative processes since probably some past life, I crumple the pages and stash them behind my the bookshelves in my bedroom.

That year during parent-teacher conferences, a teacher at my school complains to my mom about my Stephen King habit.

“El,” my mom later reports: “she said that even if you are mature enough to handle those books, which she doubts, the other children are certainly not.”

“But I’m the one who’s reading them,” I say.

“She says that the other children are taking an interest.”

I know it’s true, too. A girl I like asked to borrow The Dark Half, for example— zap— and I told her she can hold it when I’m finished.

My mom agrees to let me keep reading whatever I want as long as I don’t break them out in school. Until I come home one day to find my bookshelf pulled away from the wall, the stories gone, and the shelves mostly empty, robbed of their Stephen Kings. I feel absence lack, a kind of low horror. I loved those books so much.

2.

I’m in college, it’s midnight, I’m blazed off multiple dutches and hours of writing fragments. All the stories I present in workshops come from these late-night sessions. I mash them up and make collages, feeling like a fraud because nothing I make is linear. In class, I learn how authors are tyrannous and reflect the colonialism of their countries. A famous Shakespeare scholar tells me that she can’t grade my paper because it reads like a work of fiction, complete with building tension and climactic reveal at the end of a thesis that should have been announced at the beginning. I make corrections. Get heavy into meta-narrative. At some point, I become convinced that I can will myself into the life that I want by writing only good things. I read Chekhov, Virginia Woolf, Borges, Jane Austin, Poe. I take more lit classes, write analytical papers on those authors, close read texts with Freud and Foucault.

My girlfriend lives across the country and I’m really focused on being true to that relationship. All the time I’m lonely. Sometimes, after his shift, late at night, my best friend from high school comes over to smoke blunts— and if it gets late, and if he doesn’t want to go home yet, he’ll fall asleep on my couch while I pivot around in my desk chair and switch from talking to writing. It’s a lot of hopeless romance in pieces. I try to will the good outcome through a text. I graduate from college, assuming that I’ll soon write a novel.

Zap— with my girlfriend in Paris, a small hotel room, chain-smoked cigarettes, arguments, tears and sex at intervals. I have the thought that there are two trees in me now: one that loves, one that hates. This strikes me as a terribly important revelation. It’s a visceral, physical thing that haunts me for years.

A while later I forget how to write completely. I feel like a fool and can’t trust a thing, least of all my sentences. I work an office job, get a master’s degree, bum around tending horses and doing low-level computer programming. I begin to hate myself.

3.

Boom, I’m in my thirties, it’s almost the present.

Somehow I’m a yoga teacher and a photographer. I know that on some level I’ve made every decision in my whole life in the hopes that it would lead to better writing. But all I’ve written for years are documents that read like angsty teen journals. I edit sentences down to nothing. I manage to write a pseudo novella that tells of my woes in what I hope is a comical fashion. It’s written in fragments. I tell people that it’s a phenomenology of existential depression and a few readers seem to really like it, though it’s rejected from all small publishers and contests. I don’t blame them. It should be sampled down to a short story, really.

I take a break from writing. For the first time in twenty-some years, I buy a Stephen King novel. They’re mad expensive now, around twenty bucks. I’m like damn, really? I feel old and young. But I entertain an unlikely hope that reading them will help me to access my mind as it was during the innocence of my childhood. If so, that would be a small price. So for a month, every spare moment is for King. I read when I wake, while drying off after a shower, between yoga classes, after editing photos, in the car at red lights instead of scrolling on my phone. His writing is smooth and sometimes tedious but it moves, it’s vivid, and there’s a depth to certain phrases that way-transcends any genre; I mean much like simple fairy tale statements can speak so much about our deepest love and deceit and bravery and confusion. I find images of his books from the early nineties: The Dark Half, where two reddish black sparrows make up a single human-esque face; Night Shift, where a bandaged hand is covered in eyeballs; a blue-tinted Misery with the title in courier. These covers predate the movie versions. When I look at them I feel myself seated before the computer in my dad’s den, typing words on the all-blue Wordperfect screen that seemed like it could hold anything.

As far as this all fixing my relationship to words?

I don’t know, I mean I guess we’ll see but I feel like it worked.

Maybe our minds really do hold tunnels: doorways disguised as innocuous parts of our selves— locks opened by keys made from other pieces.

Zap.

—-

Elliot lives in center city Philly though he’s been entertaining rural fantasies. He has an undergraduate degree in English and creative writing from the University of Pennsylvania and a Master’s degree in early American lit from Vanderbilt. In a strange twist he now teaches yoga and takes pictures for a living. His first novella, imperfect though it may be, can be found on Instagram at @dayspassfast – his image work is at elliotpolinsky.com, or on ig at @_elliotp – and his yoga classes and retreats are at yogawithelliot.com . If he eats one mochi he’ll eat one hundred. his favorite tarot card is the tower.

Elliot lives in center city Philly though he’s been entertaining rural fantasies. He has an undergraduate degree in English and creative writing from the University of Pennsylvania and a Master’s degree in early American lit from Vanderbilt. In a strange twist he now teaches yoga and takes pictures for a living. His first novella, imperfect though it may be, can be found on Instagram at @dayspassfast – his image work is at elliotpolinsky.com, or on ig at @_elliotp – and his yoga classes and retreats are at yogawithelliot.com . If he eats one mochi he’ll eat one hundred. his favorite tarot card is the tower.

“Write what you know”

“Write what you know” by fiction editor, Douglas Menagh

“Write what you know” is advice every writer has heard at some point in their life. It’s a cliché, and not without reason. Exploring the known makes sense when writing about what it’s like to be someone else. The whole point of reading is to get outside your head and experience the perspective of another. But what happens when you know nothing? It isn’t easy writing when you don’t know anything, but sometimes, it’s the things we don’t know that end up filling a book.

At 19, when I took my first Creative Writing class at F&M, I didn’t know much, but I knew that I wanted to write. I also knew that I had a wholesome upbringing in a tight family, even though my parents were divorcing and I was becoming increasingly estranged from my father. I wrote a short story about that, but it wasn’t very good. Even though it was based on something personal, what was missing was the sense of really experiencing life.

I wrote science fiction and fantasy, but what I should have been doing was what one professor mentioned in passing one class. He spoke of some teachers who pushed their students to write about troubling experiences. This wasn’t my professor’s teaching style, to prompt students to tackle episodes they’d rather avoid writing about, but I think that I should have used writing to face conflict head on.

The closest I came to writing about a deeply moving experience for a long time was my thesis. After spring break during my senior year, I wrote a short story based on meeting a DJ from out of town on her last night in America. I didn’t know why after spending less than a day with a stranger, I found a feeling I had lost. Maybe it was because we talked about art and she spoke about creating from emotions. There was so much about her that I didn’t know though. What I did know was that I wanted to see her again, even though chances are I wouldn’t, because she wouldn’t be back in America for a while. After she left, I wrote about what happened with her for my thesis, even though it was still technically science fiction. Turns out writing when you know nothing isn’t easier than writing about what you know, but it can get writers closer what it means to be creative and alive.

I was 27, enrolled in an MFA program, when I decided to finally listen to my mentors and write about the personal experiences that affected me. I took their advice because it was exhausting writing genre fiction when I wasn’t very good at it. I was also tired of remaining silent on things in my life that happened to me. I’m not sure if my mentors could sense that, but I’m grateful they got my story out of me. In my manuscript, I was able to write about the DJ, how we kept in touch, and she came back to America and stayed for a while. I wrote about my sister and mother and the death of my father. I also wrote about David Bowie, because he had died, and I loved him too.

Writers are told to write what they know, but what they should hear more often is to write about experiences that affect them. To be moved by a piece of writing is to discover something previously unknown. Writing challenges readers to question their assumptions and what they think they know. The act of writing and reading can change experiences into something understandable, and beautiful. That’s why sometimes the things we don’t know can fill a book.

Douglas Menagh is a writer based in New York City. He received his MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University. He previously wrote for The New Philadelphia and has been published by Lunch Ticket and Annotation Nation.

An Artist’s Perspective on the Literature of Passion: White Heat

Under tan, stained skin

This blood screams for it

Like the whistle from your teapot

Taste me you’ll taste the truth

Wasn’t made to wait

I was made to make

Take, tear, sigh, leak for this

Drip Drip

Lips pulling my skin inside

You – me – him – you too

None of us matter

So what does it matter

We all look alike

We all stretch with impoverish

Touch me

Bind my body crush my spine

Choke my thirst with each finger tip

Tremble with each and every

Thrust

Controlled. Practiced and disciplined

Now leave don’t look back

You, you stay

Console me

I just died so good

Hurts and I love it

You do too.

I love you

But not here

You’re a means to an end

Because it’s always gonna end

But you – are everything

Devouring glances

Inhale me like life

We smell sinful

Take me again

****

Artist Statement:

Write what scares you. This is the mantra I’ve been reciting and dodging for over a year. If I wrote the truth – then I’d have to relive it – and even scarier than that – I’d finally have to let it go. So here are my baby steps. Time to look into the mirror and recognizing who I really am – now – after. Love lost left me sinking into a quicksand I like to call “identity crisis”. The transition of living as a “we” to an “I” is daunting and unfulfilled. Coping soon became realizing all the parts of myself I’d been ashamed of and snuffed out over time. All those things I’d been told I wasn’t supposed to be. Too dominant, too sexual, too sad, too emotional, too sensitive.

As a direct result of not becoming Mrs. (insert ex’s name here) – I became another me. The complex, often dark, insatiable force who bores easily and plays frequently. Perhaps I should be grateful? Say thank you? But I don’t think I will . . .

So here are the thoughts of a modern coping woman. A blend of tears and savagery

Overcoming Your Internal Critic

I’ve been thinking a lot about writing and wondering whether I have anything worthwhile to say about it.

I’ve been thinking a lot about writing and wondering whether I have anything worthwhile to say about it.

There’s always that same element of self-doubt when you’re about to embark on any writing project: “Is this going to be good enough? Am I going to be good enough?” You can read what others have written and try to do as they do. You can call on someone for advice or a helpful push in the right direction. In the end, as with few other things in life, it comes down to you and you alone.

“Writing, at its best, is a lonely life.” That’s from Ernest Hemingway, and he would certainly know. I couldn’t come up with anything nearly as good to say about writing; the best I could manage was a phrase that seems lifted out of a comic book speech bubble.

“Writing is the ultimate challenge.”

It really is.

No other pursuit faces such a daunting task with such a limited number of tools – to transcribe your limitless imagination and your innermost feelings onto a blank page, using only the words you know. The writer faces an eternal battle, with you on one side and a featureless void on the other. Everyone who views your work is a judge and every judge has his own set of criteria for whether it’s good or bad.

In a Rod Serling-like twist, your most vicious and inimical judge is always yourself.

I don’t write with publication in mind; I’ve never submitted my work to magazines; my “circulation” is usually my family and a few friends. Yet I’ve lost count of the stories I’ve abandoned because that internal critic was whispering in my ear, telling me that I just didn’t have it, that it wasn’t good enough, that I just needed to scrap it all. At those times, the ultimate challenge of writing becomes an ultimate defeat.

But by the same token… is there anything more satisfying than writing something that you like? Even if you finish it, file it away, and never share it with another living soul, you’ve joined the ranks of the storytellers. You can rub elbows (in spirit) with the authors of the Viking sagas, with the traveling bards, and with whoever that guy was that wrote Beowulf.

So maybe that’s my piece of writing advice (and I don’t feel bad giving it because I still make the same mistake myself): don’t hesitate. Just tell your stories, because every piece you complete is a victory over the void. That story didn’t exist until you wrote it. The only obstacle was the thought that you couldn’t tell it. You’ve scribbled, or typed, a whole little world into existence.

It’s the ultimate challenge, the ultimate test of our own resources.

We let the blank page win far too often.

***

From an undisclosed location in southeastern Pennsylvania, Dirk Linthicum spends as much of his free time as possible laboring away on short stories, plays, scripts, and a seldom-updated, viciously contrarian movie and television blog at ltgsabm.wordpress.com.

From an undisclosed location in southeastern Pennsylvania, Dirk Linthicum spends as much of his free time as possible laboring away on short stories, plays, scripts, and a seldom-updated, viciously contrarian movie and television blog at ltgsabm.wordpress.com.